For those who have witnessed it, it’s hard to forget the spongy moth outbreak of 2021. Over a few weeks, masses of caterpillars covered every tree in sight, leading to vast expanses of leafless trees… so early, in June! This phenomenon occurred over much of southern Quebec, and Mont Saint-Hilaire was no exception.

Aerial shot of Mont Saint Hilaire on June 6, 2021 (photo: Gault Nature Reserve of McGill University)

This summer, only one year after the outbreak, experts noted the near disappearance of spongy moths in southern Quebec. This was unexpected because while spongy moth populations rise and fall in cycles of roughly 10-15 years, once established, they usually stay for a few years. A research team led by Emma Desplans, Professor in biology at Concordia University, is interested in finding out why they left so suddenly. The two research projects taking place this year at the Gault Nature Reserve are exploring if parasitoids, and an inability to survive the winter, are playing a role.

A period of rest

Spongy moth caterpillars (photo: Alex Tran)

The spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) is an invasive insect brought to North America from Europe in the late 1800s. In the early summer, the insect, in its caterpillar stage, consumes large quantities of leaves. The caterpillars prefer certain types of trees, like oak and apple trees. In contrast, others, such as ash or red maples, are generally left undamaged. After a few weeks, the caterpillars emerge from their cocoon as their final form: the spongy moth. Luckily, the moth does not eat leaves like the caterpillars do. The forests of southern Quebec were able to recuperate during the late summer months of 2021. As the moth eased off, trees were given a break to grow their leaves back, gaining energy through photosynthesis.

An adult spongy moth (photo: Alex Tranl)

Seasonal changes and yearly changes

Seasonal periods of defoliation can be highly stressful for trees. Luckily, the short period over which the caterpillar is active allows trees to bounce back from the defoliation, albeit with less growth that year. However, if these events occur year after year, the stress could severely hinder the tree’s long-term health and could even cause death. Understanding what causes the yearly rise or decline in spongy moths is therefore crucial.

An unexpected change from year to year

The following summer, in 2022, experts registered a near-total absence of spongy moth caterpillars. Not only did the numbers decline drastically, but the caterpillars they collected had a sharp decline in survival to adulthood. Why has mortality increased? As with most ecological phenomena, the answer is complex. Many factors play into the near disappearance of spongy moths in southern Quebec.

Noa Davidai, a Ph.D. student at Concordia University, co-supervised by Dr. Emma Despland and Dr. Carly Ziter, is interested in one of those factors: mortality over the winter. Spongy moth eggs lay dormant in the wintertime. Thus, she is interested in whether temperatures below and above the winter snowline can affect spongy moth survival. The scientist will compare the data she collects at Gault this winter to that of other urban and non-urban parks of the Greater Montreal region.

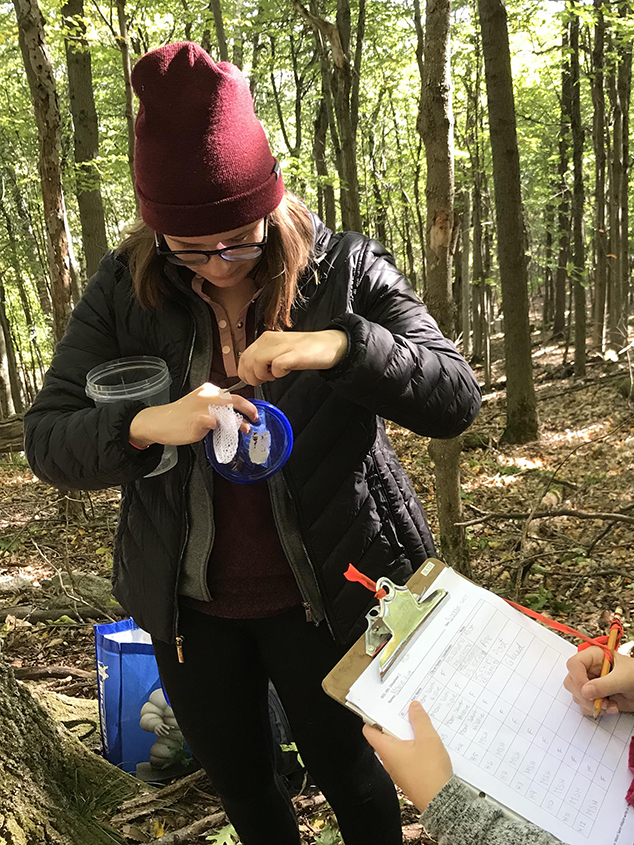

Marie-Ève Jarry prepares an egg mass for her experiment (photo: Marie-Ève Jarry)

Marie-Ève Jarry, an undergraduate student at Concordia University, also supervised by Dr. Emma Despland, studies the effects of spongy moth outbreaks on native moth species. Parasitoids, insects that live inside and feed on the spongy moth eggs, are thought to have played a role in the disappearance of spongy moths this year. As the abundance of moth eggs increases, so do the parasitoids who feed on these eggs. The researchers are interested in what happens to those parasitoids once the spongy moths are gone.

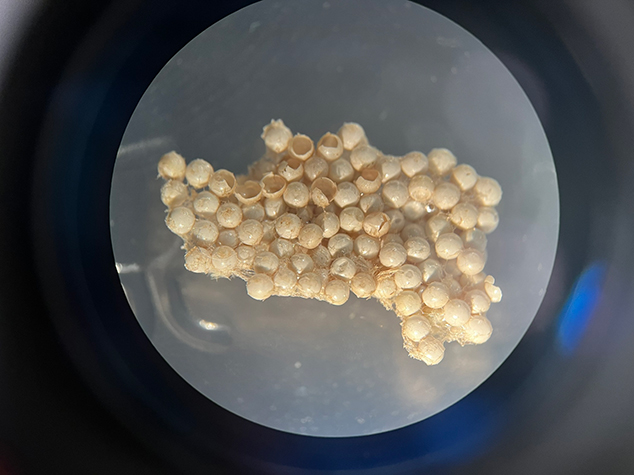

They think that parasitoids may turn to native moth species instead. To test this hypothesis, Marie-Ève and a team of researchers carefully placed egg masses from Tussock moths (Orygia spp.), a native moth species closely related to the spongy moth, on trees around the Reserve. She recently removed the egg masses from the field, which she will analyze in a laboratory to determine if the parasitism rates differ from a typical year.

One of the Tussock moth egg masses examined by Marie-Ève Jarry for her experiment (photo : Marie-Ève Jarry)

Projects like these help us understand spongy moth outbreaks so that we can find ways to mitigate the damage caused to parks in urban and non-urban settings. And, of course, so we can continue to protect the natural treasures of Mont Saint-Hilaire.

Frédérique Truchon

Communications associate

Gault Nature Reserve

Header: Photo by Alex Tran

Related articles

Invasive Species: A Study of Tench and Their Invasion Potential

August 4, 2022. To understand the potential impact that Tench might have on the Great Lakes Basin, McGill Ph.D. student Sunci Avlijaš conducted a study in 2018 examining the effects that temperature and type of lake environment have on Tench growth.